Erwin Olaf died on 20th September 2023. I wrote a number of texts for various books of his, notably for a splendid collection published by Aperture in 2014 called simply Erwin Olaf: Volume 2. What follows is remade from several of the drafts I wrote for that publication – and so is an expanded version of the text published. Of course it is out of date in some aspects: it makes no mention, for example, of the glorious series Im Wald, made after these words were written. It is also canted perhaps more toward melancholy than it would have been had it not been written at that time; but in the circumstances, I’m OK with that.

I need not explain that I was a huge fan of Erwin’s and I hope a friend. He taught me a great deal about pictures, about thinking, and about courage. Ave, Erwin, atque Vale.

I strongly wish for what I faintly hope;

Like the day-dreams of melancholy men,

I think and think on things impoossible,

Yet love to wander in that golden maze.

John Dryden, Rival Ladies, iii, 1.

The easiest way to see many important and fine pictures by Erwin Olaf (including many referred to in the text) is to go to https://www.erwinolaf.com/

Erwin Olaf takes his place among the most garlanded Dutch photographers in a generation when photography in the Netherlands is both booming and spreading out in surprising directions. He’s the leader in a rapidly evolving yet highly competitive field there. He’s a wildly successful commercial photographer, widely respected also as an artist. To hold on to both of those is perhaps easier than it was some years ago, but it’s still a hard trick to get so right. Yet Olaf always insists that he treats both equally and that each adds much in his practice to the other. He works for himself; he works for others. I’m not sure that without being told, that I could invariably tell which pictures fell into which category. That’s as he wants it. He uses the same culture, the same skill, the same brilliant restrained communication on either side of a divide which leaves many photographers floundering. What he says he says with completeness and with clarity, whichever context it goes to. As it happens, this [Erwin Olaf: Volume II] is a book of his own work; but you could quite easily take any picture from here and put it in a commercial context without doing it violence.

Again and again Olaf has demonstrated spectacular skill in the technical aspects of photography. For Berlin, long after he’d reached the top of his game, and long after he had anything left to prove, he taught himself to make carbon prints, a steep task, since carbon printing is a nineteenth century technique that is demandingly arduous to do at all, let alone to do with any kind of elegance or savour. Olaf is a perfectionist photographer (he has spoken of the pleasure he gets from the flawless world in his viewfinder compared to the messy one outside it) and he starts always with the craft aspects of what he does. Large format cameras, digital manipulation, complicated lighting sets-up — he won’t use tools unless he can use them specially well. And he uses them all. He actively enjoys his own mastery.

It is routine to say of such people that they ‘make it look easy’. If you were to look only at the pictures here in this book you might think that this effortless cool, this almost constant stillness, this evenness of temper justified the cliché. But I don’t think Olaf makes it look it easy. I think it is our mistake to look for ease in the full and difficult range of a photographer who, if nothing else, has always managed to work the subtle complexities which interested him into pictures intended for less than subtle use. Even in a commercial job, Erwin Olaf takes it for granted that pictures should have depth and heft and that they should hit hard and be full.

It so happens that before I sat down to write these words I was leafing through photographs of Olaf’s while listening to an old recording of Maurizio Pollini playing late Beethoven piano sonatas. Pollini perfectly understands that late Beethoven isn’t Bach. Yet he delivers the most daring experimental music of its day, the music that effectively wrung the neck of the sonata form, on a rock-solid bed of mathematical assuredness. Pollini plays Beethoven op. 111 like soaring boogie-woogie on a heavy base of Buxtehude. Crucially, neither element trumps the other. Just so, Erwin Olaf can deliver contemporary reflections on Vermeer knowing that for many of us visual culture doesn’t go much beyond recent advertisements for Diesel jeans or Lavazza coffee.

In a number of series over recent years, Olaf has situated people alone, wrapt in inner contemplation either erotic or sad. These things have their antecedents in film or novels — and specifically in Vermeer — and they have been very well received as somehow reaching a shared level of deep melancholy beneath the gaudy sales patter of our must-rush era.

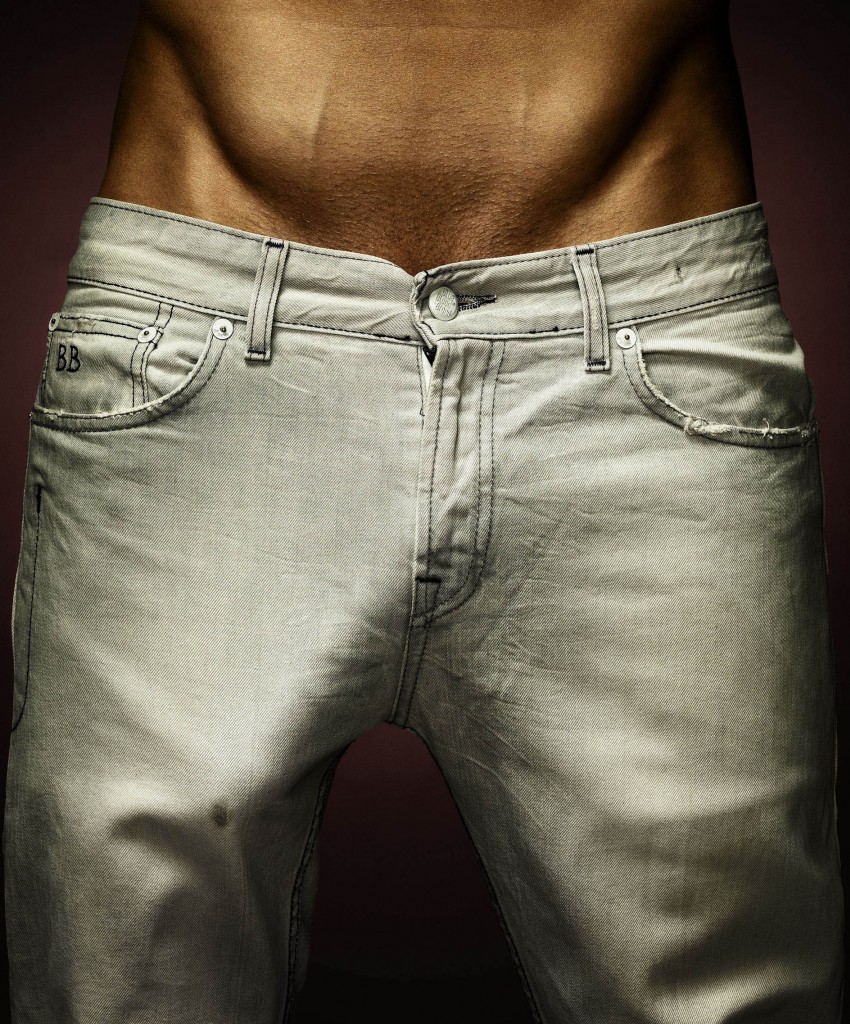

Olaf did make those pictures and they do represent something that struck deep. You can see many of them in these pages [again, I’m referring to the book, Erwin Olaf, volume II]. But before that he had also made a frankly bawdy series of close views of large cocks seen straining and bulging through jeans so tight they can barely restrain them. Those were pretty close to porn; but they were also striking for their wit, a certain joie de vivre, for unabashed hearty pleasure in things bodily. Olaf has worked very successfully with dance groups, often portraying them nude. (He has, though, had less luck with footballers. I remember a series in which Olaf managed to make the Dutch goalkeeper Edwin van der Sar, a great athlete but an earthy one the very opposite of showy, appear as camp as a row of boy scouts.)

This Rabelaisian strand has not disappeared in Erwin Olaf’s later work. It has gone under; it’s under the chilliness of pictures such as the Keyhole and Waiting series. It’s under the longing wistful restrained sexuality of the Hotels.

The super-sophistication of Olaf’s late pictures that we have here — perfect 70s retro detailing in the furnishings, models of such superiority that they seem contemptuous even of the photographer; the whole made to be seen in fine art exhibitions of branded measured urban metrosexuality — is built upon layer upon layer of a different kind of photography. Remember that Olaf made in his early days a lauded book of portraits of people with mental disabilities. He’s made several unrestrained series where the bawdiness went well over the edge into bad taste — try a lookalike Princess Diana with the three-pointed star of the Mercedes she died in embedded in her flesh, for example; or try his variant of that hoary old pun of a picture where the nude man holds at waist height a champagne bottle which happens to be foaming up…). He’s made many more series where the ‘good taste’ was absolutely under control but the subject matter was close to wild: an ordinary family where parents and children are in head-to-toe black rubber (Separation) or a hysterically savage parody of the nip-and-tuck business in which a couple of bored ladies have comically extreme deformations of the features (Le Dernier Cri). Olaf has been face-to-face with lack of control and used to enjoy a Saturnalia. The cool is somewhat tempered by that; without all that hotter stuff behind it, the cool is just…cold.

Erwin Olaf made dozens of workmanlike steady portraits for commercial clients before he started to make the heightened, almost parodic portraits of his later years. I remember in particular a portrait of Princess Máxima (of the Netherlands) staring out of a window in a grey trouser suit, the very soul of Protestant royalty, respectable as could be. No doubt it was shot in a palace; but palaces look like five-star hotels because five-star hotels try to look like palaces. Only years later were we able to see that that serious picture had become the prototype for the unfulfilled mysteries of Olaf’s Grief series. I doubt that her Royal Highness’ head was filled with quite the cocktail of sex and longing and memory that Olaf put into the later series; but then, why suppose? OIaf found and worked a seam where melancholy was itself an attribute; the virtue of having once lived wildly.

I suppose that’s the point. Erwin Olaf has made no secret of two vital facts in his make-up. The first is that he is robustly gay, of the generation which knew the wildness before that world imploded with the fear and the reality of HIV. Olaf has himself said of his recent Berlin series that it was in part inspired by a terrible wistfulness for the Berlin he once knew, where he partied with the best of them.

Erwin Olaf also has emphysema. He sometimes struggles for breath, and his condition is steadily worse year by year. He asks for no great pity about this; it is a fact of his life as being a redhead might a fact of another’s. But there is no doubt that his lungs make Olaf acutely conscious both of the passage of time, and of the destructiveness of the aging process. For a person who believes as he does resolutely in the need for perfection and the value of it, a slow disease is a searing affliction not only for its physical effect, but for its constant reminder that the battle can’t be won. Olaf carries around his own pitiless Et in Arcadia every day. Olaf once made a searing triple self-portrait of himself aging. It was digitally done, of course, but it could just as well have been made in Dorian Gray’s attic.

Nostalgia, melancholy, outright sadness: they’re not abstractions for Erwin Olaf. They’re his daily bread. That man laboriously climbing Hitler’s private staircase at the Olympic Stadium, out of the darkness, and into the light? That’s Erwin Olaf, in another self-portrait, for whom a staircase is more of a challenge than it would be for you or I.

Erwin Olaf has elevated melancholy to a height reached by no other photographer. His melancholy is not that of Mathilde de la Mole (one of Julien Sorel’s two great lovers in Stendhal’s Le Rouge et Le Noir), “languissante d’ennui au plus beau moment de la vie, entre seize ans et vingt.” Olaf’s melancholy comes not from boredom, but from memory. For him, it’s not that it is fashionable to be blue. It is that Olaf has all that it takes to be fashionable; only his register is inescapably sad. When it comes to sadness, he knows whereof he speaks.

Few photographers deal as completely as Erwin Olaf in stillness. In a lifetime of making still photographs, he has only rarely even made the suggestion of movement, let alone depicted the thing itself. As we turn the pages of later works assembled here, we see a couple of figures laboriously climbing stairs, and for movement, that’s about it. Everything else is poised. No wonder one of his series was called Waiting. Not for Olaf the idea that a photograph freezes flashing glimmers of time. In series after series — and not just from these more recent ones — Olaf has invented a way of slowly filling photographs with deep melancholy, like an eye slowly filling with tears.

It is worth dwelling on this rejection of Olaf’s of photography’s customary fractions of a second. We are used to viewing pictures too fast. In the present-day never-ending flow of images, all good photographers look for ways to slow down viewers, to hold for long enough the twitching, jumpy eye that has become the standard receiver of photographs. Olaf is far from alone in that regard, although the particular solution is his. Olaf discovered that by making slow pictures, pictures which built mood and atmosphere, he had a chance of staying known to his audience. Otherwise, he was gone in that familiar flip of the thumb which turns thirty magazine pages in one go. Years ago, Olaf invented slowness as his brand, and it has served him well. A number of his great series — Hope; Fall; Rain; Hotel… — are built on the pause. We see a moment, of course — that’s all a photograph can do. But Olaf’s moments are big ones. There’s a little English phrase for that odd awkwardness when a hubbub of conversations, in a restaurant, say, or at a crowded party, all stop by chance at once. “In that hush an angel passed.” Erwin Olaf photographs those moments.

In his work in film, too, Olaf, has taken a rhythm slower by far than is usual. In Desire, a caper of an ad he shot for a firm called Vente Privée, in which a succession of well-heeled ladies struggling against boredom in a prosperous suburb are enlivened by the handsome delivery boy and whatever it is that he has in his box, the ultra-slow narrative was a silliness. It gave Olaf a witty way of wallowing in the languid mood of long afternoons where nothing happens beyond the silent growth of the capital in the bank.

If slowness suited Olaf as a branding trick at first, it has become something far richer. Olaf has changed; he used, by his own admission, to be a considerable extrovert. Now, partly under the sustained pressure of the long-term diminution in his health, he has become more reflective; contemplative, even.

By the time of his Berlin series (2012), everybody could see his skill at the reexamination of histories and myth. Berlin is full of quite open allusions: here is Jesse Owens, the famous athlete who embarrassed the racists in the Olympics in 1936; here is a vision from Christopher Isherwood via Liza Minelli, here another from Christian Schad or Otto Dix via Pina Bausch. But Olaf’s method has never been to say “look at the way previous people have looked at my same subject.” Instead, he shows that considering anything in depth is always also to consider the previous ways we have been told about it. Done fast, as Olaf learned to do it for commercial clients with limited patience for complexity, the risk is of borrowing a look or a style without the inner weight. Do that examination more slowly, as Olaf has liked to do it over many years in his own personal works, and the result is a lovely thick impasto of solid culture in every picture. The slowness has become an invitation to the viewer to think more deeply. We’re not asked, as we turn these pages, to see only the pictures before us. We’re asked to check our view against what we already know.

Checking previous culture has long been a mark of Olaf’s method. He has made brilliant reworkings of Dutch history paintings. His 2011 series on the vicious siege of Leiden of 1574 (every Dutch schoolchild knows about it), commissioned for the Lakenhal Museum there, is long overdue a new showing. An older series called Ladies’ Hats (1985), took the kind of heavy velvet hats of the Rembrandt self-portraits and placed them on nude upper body studies of men: classic Olaf, for simplicity, technical perfection, and a lovely twist to bind the past and the present together.

Previous culture does not flash through us. Previous culture seeps into the very fibres of who we are. That’s why Olaf’s allusiveness and his slowness go hand in hand. He has been able to ask us to consider not merely the overt culture of big moments in history or big painters, but the more concealed culture which makes up the person. Olaf has done a lot of work on family life (his film Separation, for example, of 2003, or the films which are seen within the Keyhole installation). Sexuality, memory, identity: these are the big themes of Olaf’s pictures because they are the big themes in of all of us.

Some time ago, he started mining his own work as well as that of others. The 2009 series Dusk, for example, was inspired in part by the pioneering Hampton Institute Album of 1899 by the wonderful American woman photographer Frances Benjamin Johnston. But when Olaf went on to make the companion series Dawn (we see some of each series here), he looked at Blacks, his own series of some twenty years before, and reversed the tonalities to a pale washed out whiteness that was wholly new. Blacks had the gorgeous rococo complexity of Grinling Gibbons; in Dawn that has become an echo, visible in a carved marble eagle, an alabaster ewer, or an ornate chair back.

This reworking has become a central part of his practice. Not only has he made a lot more films since the turn of this century; he has started to braid the films and the photographs much tighter together. The fullest development of this so far is the spectacular weaving of the several parts of the Keyhole series, in which his own work seems to have become the stimulus for the next part of … his own work.

The Keyhole photographs sometimes put us outside the scene, over the shoulder of someone staring through the keyhole, and by necessity unable to see what they see. Then sometimes we have jumped and have become the person stared at. Adolescents often feel that they are being looked at all the time; an uneasy mix of their own desire to be seen and a hesitation, a wanting to go back to that childhood refuge of being unaware of the gaze of others. That’s where the Keyhole series started. But in the two films that Olaf now projects within the installation that makes up the full piece in its latest form, he has moved further. A man takes up a child for a cuddle. A woman does the same. We see nothing untoward, yet there is no escape from a sense that all is not as it should be. Olaf is in the territory where psychology has coloured the pre-psychological readings that were familiar to all. All families have stories, he seems to say, but sometimes even the people in the family don’t know (or can’t admit?) what they are.

The Keyhole series is in one way very Dutch. When I asked him about this, Olaf cited the novel Van oude Mensen en de Dingen die Voorbij Gaan (Old People and the Things that Pass), by Louis Couperus, from 1906, in which a couple, retired from the Dutch service in Indonesia retire to The Hague. Everything seems fine, until slowly a horrible murder in their past is revealed. Olaf doesn’t need to reveal the murder: he knows that we have all read novels like Couperus’ or parallel ones in French or German or Czech or Russian or English or whichever language we did our reading in.

As it happens, the original tiny seed of the Keyhole series came when a child model on a shoot peeped through a real keyhole. His mother, present as a chaperone, put him on her knee. It might have been nothing, a blink. But every photograph starts as a blink. How big they grow is what the photographer gives us beyond that.

Erwin Olaf has become vaguely dissatisfied by the surfaces of photography, and finds in two parallel forms a relief. Photographs, protected by glass or perspex, always have an impenetrable sheen which to some extent repels the eye. We bounce off photographs, even when they are as beautifully crafted and as slow to read as his. When he works in film, that no longer happens. In film, we remain in contact with the artist for the few minutes that we watch; and Olaf feels that gives him a much better chance of saying what he wants us to see.

The extraordinary flower studies of the Fall series are a clue to Erwin Olaf’s other new direction. Still-life is by definition slow. As an artist, you pose those flowers with endless patience and they are only worth a viewer seeing if the viewer can give them time in return. As part of the vaguely hotel-derived interior-design schemes of that rich world Olaf has been describing for many years, in which money can’t buy happiness, studied vases have their place. But they become more than that in the hands of an artist for whom photography can no longer do all that he needs. At best, these studies, like the alabaster vase in Fall and a number of other pieces, show Olaf beginning to flirt with sculpture.

The little film of Karrussel (2012) is a move in the same direction. It uses a variant of that same clown that Olaf has used many times before. Clowns in Olaf’s work are Everymen, their exaggerated facial expressions standing for all of us, and their traditional compound of happiness and melancholy the perfect vehicle for the complex mix of emotions that Olaf likes to depict. In the film, we move steadily around the clown figure and his possible accoutrements, exactly as visitors to galleries of sculpture move around the pieces, the better to see the flex and bend of the material as one curve becomes another.

When I asked Olaf about the profile studies from the 2013 series Waiting (of which some are here), which very strongly made me think of the profile heads on old coinage, he laughed. I didn’t know it then, but Olaf had been working on the “Dutch face” of the new Euro coinage (the shared currency has one side used by all member countries, but each national mint is allowed to issue a design of its own for the other face), shortly to be released. It’s a great compliment to be asked, of course, but for Erwin Olaf it’s more than that. It’s another move towards sculpture, and by the same gold-and-silver token, a move away from photography, too.

Erwin Olaf is a perfectionist photographer and a virtuoso one who starts always with the craft skills of what he does. He has put together a wonderfully coherent visual language. To do that, he had to slow the photograph down until we learnt to look with the same slow steady respectful gaze that we reserve for film or sculpture or old paintings. As the creator of a host of pictures of great skill and beauty (not to mention wit), it may be that his larger achievement is that Erwin Olaf has never accepted that photography should be as slight or as quick or ultimately as trivial as the tendency of the time dictates.