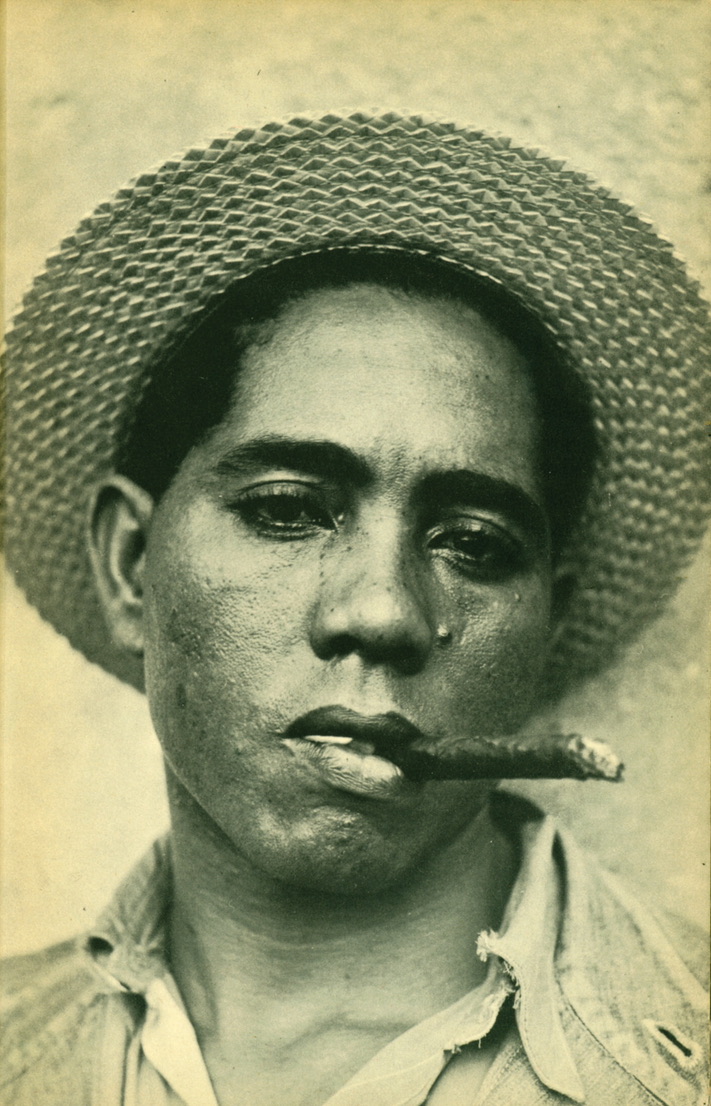

A stevedore photographed by Walker Evans in Cuba in 1933. Evans’ time in Cuba was interesting and complicated – there’s a fine essay by John Tagg in Photographies in 2009 to give just a taste of how complicated, and it’s there I refound the picture.

Great photographers control our readings of pictures. See how two blemishes on the left ( his left ) of his nose, one smaller by the corner of the eye and one larger by the nostril, and the line of freckles on the right ( his right ) of his nose simply demand to be read as tears running down the face. There’s even a glisten from the eye to that larger lower blemish, and a runny-nose gleam along the philtrum. The hat is an obvious halo, and the beautifully highlit golden face plainly alludes to religious imagery, too. The absence of background says this is a face of sorrow about all such people not just this one person. A secular saint, then, the martyr of the long politics of colonialism and the plantations, and the short politics of what Tagg called “the fading days of a brutal dictatorial regime propped up only by the money of American banks and corporations.” It’s all there in the picture – because Evans took responsibility for our reading of the details. They’re there to be read.

And yet. It seems that Evans was maybe not particularly interested in Cuban politics nor in the plight of its underprivileged people. He was sent there by the Philadelphia publisher J.B. Lippincott to provide illustrations for a book by the radical American journalist Carleton Beals entitled The Crime of Cuba, a book which squarely put much of the responsibility for the corrupt dictatorship of Gerardo Macheda on the United States, and on American imperialism. Beals had worked all over Latin America and had been very involved in the left-wing intelligentsia in Mexico, where (by the way) he apparently had a relationship for some time with Tina Modotti’s sister Mercedes. Evans travelled separately from Beals, but was glad to get the gig. He stayed longer in Cuba than his contract specified because he became friends while there with Ernest Hemingway who paid his expenses for an extra week. In an interview years later, to the Yale Alumni Magazine of February 1974, Evans said of the Cuban dockworkers he had photographed “Those people have no self-pity. They’re just as happy as you are, really.”

Evans made great work in Cuba. This is one of many studies of dockworkers, for a start. He learnt a lot, including the use of several different sorts of cameras. He seems to have been particularly interested in the work of Eugène Atget at the time, and there are fine studies of Havana shopfronts which are very Atget-derived or Atget-conscious. It is certainly possible to make good arguments that Evans was a man of the left, even if non-aligned. But it may be wrong to read that political inclination into every picture that he made. In another interview, in 1971, he said “It was a job. It was commissioned. You must remember that this was a time when anyone would do anything for a job. This was a job of a publishing house publishing a book about Cuba and a friend arranged that I should do the photography. So I grabbed it”.

I think there’s a lesson there. I like nothing more than reading a picture, in great detail, and I’ve done it all my professional life. I’m glad to think that this stevedore looks like he’s weeping. I think it’s a great and very moving portrait. But I also think we (and I) need to be careful when inserting our own readings into photographs. It’s true that I am completely entitled to read this as a study of an oppressed working man – and a wonderful one, at that. But perhaps it’s not right to say that’s what it is. Evans didn’t seem to think so. It may just be that Evans wandered lazily down to the dockside in the heat, in the intervals of drinking with his buddy Ernest, to point his camera at the nearest subjects who would get the job done.