Well, here is a rare and rather enjoyable thing. I’m used to writing about pictures whose author is known, whose subject is known, whose date is known, whose cause is known, whose customer is known or any or all of those things. The experience starts as that which is familiar to anyone who has finger-walked through shoeboxes of old post-cards, or cartes-de-visites or stereos : here’s something that catches my eye – I wonder what it might be. If it has a place in photographic history beyond what I can see, that might be interesting; if it has a connection direct to me, that, too, might add something. But without more evidence, it’s just me and the pictures, eyeball to eyeball.

And what pictures they are. There is something about these kids, in the tense pull between still, even stilted, poses and gestures and clothing against the lively contrarian energy bubbling up beneath their superficially calm faces.

These portraits of children were taken to the PhotoLondon art fair in 2024 by the dealer Roland Belgrave who asked me to write something to accompany them. Almost all we know so far about this group of posh children is in the pictures themselves. There is one exception, itself helpful. We know that they come from the files of Adolphe Braun. It says so on the backs of several. Braun is relatively well-documented. But Braun, as well as being a person, was also a company. These pictures are not among those known to be by Braun the person – and therefore may most likely properly to be ascribed to Braun the corporation. We simply don’t yet know.

Adolphe Braun (born in 1812, died in 1877) was originally a textile designer. (Several photographers came into the new medium through that same route, among them Charles Aubry.) Braun came from Mulhouse, in Alsace in Eastern France, a centre of printed cottons to rival the English producers. A promising early career in Paris, where he had been sent to develop skills and a network, was cut short by the death of his wife in 1843. A widower with three small children, he came back to Mulhouse and gave up the independent or freelance route by becoming the in-house designer for Daniel Dolfuss-Ausset, a major figure in the textile industry, but also an enthusiastic early-adopter of photography. Dolfuss-Ausset’s other passion was the high mountains, and specifically the study of glaciers. Not only did he pay for a hut on the Aar glacier in Switzerland; he brought daguerreotype photographers there to make some of the very earliest pictures made on a high mountain summit. He was instrumental, in fact, a little later, in the early 1850s, in persuading the Bisson brothers into the Alps. The likelihood is that is it was Dolfuss-Ausset who persuaded Braun into photography.

Adolphe Braun took to that as he did to everything else, doggedly and ultimately successfully. In 1854 he produced a book of 300 plates (beautiful deep albumen prints from collodion negatives, admirably skilfully done for such an early stage in a new career in a new technology) of flower studies nominally issued “à l’usage des fabriques de toiles peintes, papiers peints, soieries, porcelaines” – for the use of makers of printed textiles, wallpapers, silk manufacturers, or makers of porcelain. As one historian has put it, Braun’s Fleurs Photographiées were ‘a design resource for the French luxury industries’. But they were taken up, among others, by the influential critic of photography Ernest Lacan. As a result, they were also appreciated as decorative art objects in their own right. The flower studies became the bridge for Braun. Before the album of 300 of them, careful patterns based on flowers had long been a staple of the printed-cotton trade – and Braun had certainly worked on many of these long before he became interested in photography. Once they were published, Braun was quickly accepted among the first rank of photographers – and, as befitted an ambitious professional in a boom market, expanded both his subject-matter and his technical resources enormously.

From the 1860s, Braun made studies of animals, genre scenes, mountain panoramas, topographical studies, still life. These were all popular subjects for an expanding middle-class audience. He became adept (and enormously prolific) at stereoscopy, took out a licence to operate the Pantoscope (a patented English panoramic camera), learnt and used the Woodburytype process, and bought the rights to another carbon process from Joseph Wilson Swan. In a period of constant technological upgrades to photography, he checked every new improvement.

Braun was not necessarily interested in his own eye being recognised and admired: his main commercial speciality became the reproduction of art works. That sounds a dry business – but it was perfectly timed for the great expansion of travel through steamers and the railways and the expansion of education through travel. Every new art school needed sets of Braun reproductions – and some still have them. Indeed, Braun allied himself closely to the railways. He made albums of the places they reached, and he also made, in the Gotthard, a remarkable series chronicling the feats of engineering it involved to build them. As a result of all these expansions into new branches of his field, Braun became a considerable entrepreneurial success, and his corporate holdings in existing photography grew and grew.

In effect, he was an entrepreneur in the new media of the day, always ready to check a new trend or build a new market. The Braun factory at Dornach, outside Mulhouse, was steam powered (for such things as grinding the pigments used in carbon printing) and was regarded as one of the great photographic establishments of its day. A busy working photographer in the present, his previous work became the basis of a stock-photography operation and as reproduction became easier and cheaper, he made sure he was always on point for the imagery which customers wanted. He hired his close family as camera operators; from very early in his photographic career, his brother Charles and his son Gaston were working for him. Both worked on the strongly patriotic Album d’Alsace in which he made a record of the great sites of his own region. (Remember that Alsace was made over to Bismarck’s expansive Germany in 1871 after the humiliations of the Franco-Prussian war, including the French defeat at Sedan, the capture of Napoleon III and the siege of Paris. Alsatian patriotism was a much more live sentiment in the 1870s than most English speakers are likely to recall.) More relatives were added to Braun’s operation through the years, as well as leading professionals, poached if necessary from existing photographic operators.

By the end of his career, in the 1870s, it becomes perfectly possible to trace a Braun corporate history. For our purposes here, this would notably contain a note that Gaston Braun, his son, married the daughter of the favoured society portraitist Pierre-Louis Pierson and that Adolphe Braun bought into their shared studio under the name Ad.Braun & Fils. That reformed under Adolphe Braun & Cie., and eventually became Braun & Cie. which survived well into the twentieth century as one of those many ‘applied’ photographic companies with a similar genesis in the entrepreneurial exploitation of the great new medium of the nineteenth. As such, the Braun history is parallel to that of the Alinari in Italy, maybe to Francis Frith in the UK or to Underwood & Underwood in the US: in modern terminology, these are not so much artistic careers as business models seeking to marry customers to new technologies and new markets.

In 1871, after Germany invaded and occupied Alsace, Braun made a series of studies of a figure of Alsace, a striking female representation of the uncrushable regional identity, like a more local Britannia or Marianne. This became and remained very popular, being reproduced in formats large and small and reappearing in various guises in painting and even on ceramic plates. Again, the photographer has allowed the model, under a perfectly respectable, even demure, exterior, to exude a certain fierce independence. The German authorities felt so, any any rate, as they are known to have tried to discredit the model by claiming her to be the girlfriend of a German officer.

The last connection to be made is not with Braun himself so much as with the younger partner of his company, Pierre-Louis Pierson. Pierson became the society photographer of Napoleon III and by that fact the society photographer of the Paris of the Second Empire. By the later 1860s Pierson’s studio in the Boulevard des Capucines (with his partners the Mayer brothers) was frequented by everybody who was anybody. Pierson’s long, long collaboration with the Castiglione (briefly mistress of Victor Emmanuel and for a longer time of Napoleon III, and a considerable figure in nineteenth-century history in her own right) has attracted the notice of several fine historians of photography as one of the very early partnerships in which a woman came to direct her own photographic autobiography – taking charge of the mise-en-scène to represent herself as she wished to be seen. Although those particular pictures remained private for many years, no doubt that Pierson knew how to walk the tightrope between proper and informal and that his sitters were encouraged to act themselves out to the camera at least as much as they were expected to dress and be accoutred in the manner of their class. It may be that he learnt some of that from Braun’s earlier successes of the kind. Wherever it came from, I see a lot of that nice balance in these portraits.

So. What do we have here, reaching the market at PhotoLondon in the hands of Roland Belgrave?

Two little boys in a studio, brothers, maybe twins. They wear luxurious clothes based on the military frogging of a hussar or a dragoon (complete with miniature gaiters), softened by a white curly frill at the collar. Their hair has been ruthlessly brushed, probably within the last few minutes, just before the picture was made. I suspect a governess remains inches out of shot. The hair cut slightly long, just long enough to cover the ears but cut high over the nape, identical side-partings. The boys look at the camera with what looks like a touch of hauteur – but I think is more likely apprehension. The elbow of the standing brother rests on the shoulder of the seated one and there is no space between them. Together they have a mass, a solid girth across the middle which makes them less frail than they might otherwise be.

Hard not to be enchanted by these wonderful portraits. To a modern eye, they have something of the feel of Diane Arbus: we get to stare at specimens from a life lived otherwise. Picture after picture with a lovely triple combination of highly polished luxurious conventional clothing marking very high social status; the visible workaday evidence of the workings of a busy studio; and the utterly compelling – and slightly weird – gaze of these children facing us over the gap of years.

Our prints come from a substantially later printing of a group of portraits of children – associated with Braun in pencil annotations on the back. They bear numbers, probably negative numbers, either on the images themselves or on their backs. Those numbers have not yet been matched to any list.

The children are certainly well-to-do. Their clothing is fine, even super-fine. They have deeply expressive faces, certainly sometimes a little apprehensive about the frightening business of being photographed, sometimes a lot more confident than that. I assuredly see disdain in one or two of them; and one (the little girl whose head is cradled by the respectfully bowed assistant behind) looks like she has just been told off one time too many. Don’t move. Stop wriggling. Look at the camera. One instruction too many – and out came that glare. Their expressions are what first held my own eye: direct contact with young people a century and a half ago is still pretty uncanny. There is some business going on between singles and pairs: two girls in matching outfits, darker above and lighter below. The smaller one has been told to hunch her legs up uncomfortably to bring her eyes to roughly the level of her (putative) sister’s. Those gentle respectful servants I suspect belong to the studio and not to the children. It looks like they use a practised over-and-under grip, the grip of people who have held a hundred squalling children for the relatively long exposure time required. Their clothes look arty-workaday rather than grand livery or uniform. No doubt those assistants were fated to be blown away in a nineteenth century forerunner of Photoshop – double printing or overpainting – as they would surely not have been intended to stay in the view.

I wish I knew more. The children are nicely behaved, all of them. But that’s for the picture: the child is itching to get out. The eldest of the young ladies, in her bonnet and richly layered skirt, has mastered the rudiments of poise; but even she, you can see, is daring the photographer to need another plate. They remind me of many photographs and of none. In the end we don’t know. But I defy you not to enjoy meeting these kids. They’re splendid and yet slightly weird. They’re completely of our own own acquaintance and not at all.

I’m sure a costume historian will be able to date them more accurately, but they seem to my very approximate eye to be from the 1860s or maybe from the 1870s. The prints themselves are considerably later and are silver prints, not the original albumen. I suppose the prints to be from 1910-1920, although again scholarship has not yet been turned loose on them. The same historian will correct me, but the children look to be wearing expensive and well-made clothing, as clean as could be. Remember that nineteenth century clothes were heavier than our own (no central heating) and tended to be worn far longer in the absence of labour-saving washing machines. It’s not at all rare to find heavy creasing and soiling in nineteenth century portraits, and these have almost none of that. Even allowing that they spruced-up for the pictures, these children are turned out in high style. They had lots of servants, whoever they were.

Many elements recur: the footstool occurs often. The heavy turkey carpet flung over a table or lectern to lean upon through the long exposure; the chair with tassels on its shoulders; the straighter chair with barley-twist members and heavy nails to its upholstery; the spindly metal chair. These things are fairly standard studio props of the time: used as much for steadying wobbly sitters as for any intimations of class or caste. The carpets are not always sharp, but they seem to recur as well.

There is also just visible in the picture of the two boys a metal stand, seen only as an extra leg under the chair. That is is also seen again in the series. I even wonder whether the various props of childhood – the hoop, the ball, the hobby-horse, the dolls – were not also studio props. They don’t seem quite to entrance the children as they would were they their own. At first sight, we’re not going to get so very far with these. But wait.

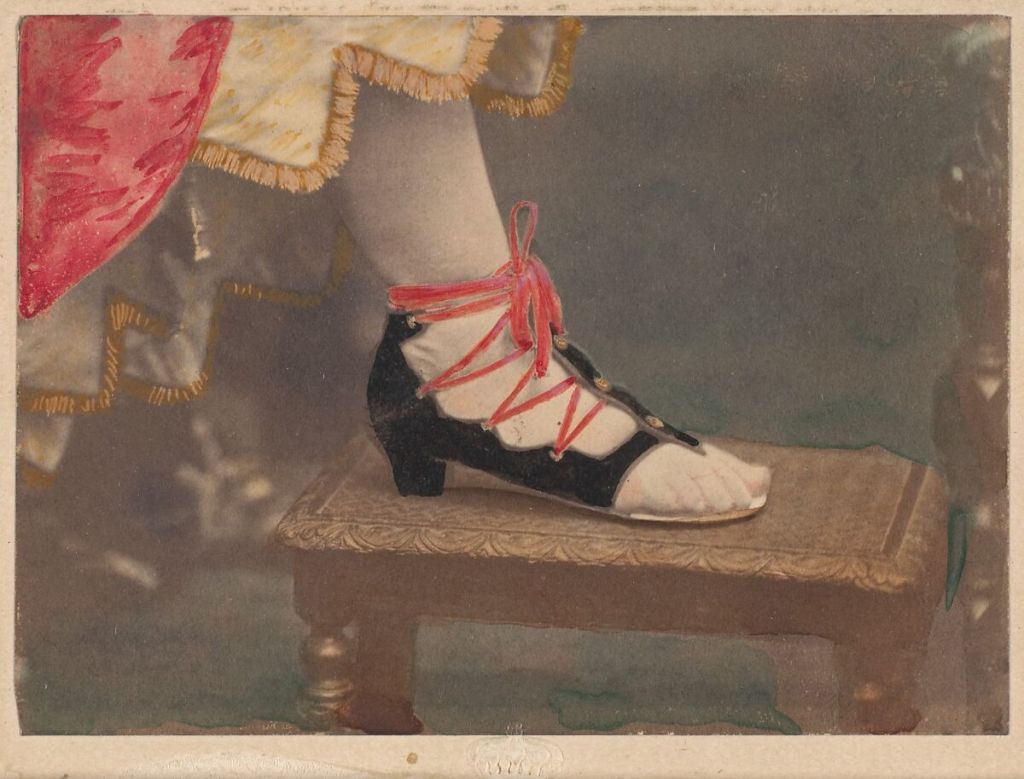

I think I’ve seen that footstool before. It’s only a little footstool, not rare, not fancy. But it irritates me. I can’t find it, can’t quite place it in memory. But I’ve been thinking of Pierson and it’s worth a trawl. Bingo – and in close-up! In the collections of the Metropolitan Museum, a group of pictures for that time risqué – even now oddly provoking. The Countess of Castiglione’s foot in a curious shoe, credited as it should be to Pierre-Louis Pierson. Laced and buttoned, with the toes exposed and a low heel. The Met calls these shoes Les Cothurnes – a rare word normally translated as ‘half-boot’ but sometimes used to describe those vaguely Roman military sandals with endless criss-crossing of lace up the calf. But I don’t really care about the shoe any more – although I nod once again in passing to the Castiglione’s superb flouting of convention. The shoe is resting on our footstool. I’m sure it’s the same.

James Hyman Gallery.

And there are others, at the Met and elsewhere. The fine English gallerist James Hyman showed a variant print of the same shoe on the same footstool, this time without the overpainting, in his splendid exhibition devoted to the Castiglione (June-August 2022). So I look there. His website is almost as well-ordered as that of the Met. In another print, the Castiglione is in deep mourning. She turns her back on a little cluster of studio equipment to be cut out of the finished print when the time comes. A black curtain. A low support of a recognisable shape, metal, curly. And that support, although it’s far less clear than the footstool, might easily be the one propping up our little child here on the hobby-horse and lurking in several other of the pictures here. The height which we see clearly in the Castiglione picture would explain why it was used. In the picture here, we see it only as a shadowy structure below the horse and therefore not obviously useful for steadying the subject. But once we know how tall it is, we see how it’s height would be all-but concealed behind the centaur of horse-and-child and yet still offer good support through a longish exposure.

James Hyman Gallery.

It goes on: the same stand clearly appears in several Pierson studies of a boy with curiously brushed-out hair (L’enfant Blanc) in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum. In another view by Pierson of the Castiglione from the Hyman show, the Countess reclines on a heavily-embroidered straight chair with heavy tacks spaced exactly as they are in our pictures here. Is it definitely the same chair? I couldn’t swear to it, but it looks too much like it to be a coincidence.

Plainly, more research is needed and more research can easily happen. Who are these children? That seems the first question. These are later prints, probably – as I say – of the period 1910-1920, and they are silver prints not the albumen prints they would originally have been. We don’t know why they were re-made, and we certainly don’t know why the finishing and finicking – which would have removed the two solicitous young men holding still the heads of a pair of very young sitters in one picture, and probably removed also that intriguing metal stand which props up several of those sitters most likely to wobble – was never done before these were reprinted.

It may well be that some of these faces recur, in photographs or in paint and can be certainly identified (although not yet by me).

But I think we have seen enough to believe that these pictures come from the studio of Pierson, society photographer to the Deuxième Empire, and these haughty children are absolutely the kinds of people he specialised in working with. They’re wonderful for character and that in itself might be enough to say they’re by Pierson. The connection with the Braun name is easily explained. The Braun corporation is in question, not the person. Pierre-Louis Pierson was Adolphe Braun’s son-in-law. Adolphe Braun invested in Mayer & Pierson, and Pierson was eventually to be a director of the Braun firm. These pictures were to be held in the Braun archive, reprinted for sale in the Braun darkrooms or later on the Braun presses, marketed and sold in Braun catalogues. The connection with Braun is real. But I don’t think they were actually made by him. It hasn’t been proven yet, but there’s little room for doubt. These are portraits of super-privileged children – maybe even imperial French children or royal European children from beyond France – by Pierre-Louis Pierson, whose glittery Paris studio was to become one outlet of the commercial empire that Adolphe Braun built.

A treat to read. This is so thoughtful and insightful. Thanks.

LikeLike

Wonderful piece. Thank you very much for posting it.

LikeLiked by 1 person