If you visit the website set up to showcase Bradford as the 2025 City of Culture, the very first page that you come to – at least at the moment (February 2025) – celebrates the major photographic commission awarded to Aïda Muluneh and the resultant exhibition at Impressions Gallery. Those websites are not sequenced by chance. This means in effect that Muluneh can be considered the lead visual artist of the City of Culture. There is an exhibition of David Hockney’s joiners and the later multi-screen films he derived from them at the newly reopened National Science and Media Museum, the sad relic of a once-brave museum which has shifted its mission over the years from its collections to the cheery ‘experiences’ it can offer. Hockney is a leading son of Bradford, and his joiners are always well worth seeing. Yet I venture to open these lines by asking this : how many people reading this had any awareness of Muluneh’s show? I wish I had the attendance figures, but how many people have visited it so far – perhaps excluding Yorkshire schoolchildren on worthy trips?

Something has gone wrong. Nomination as City of Culture for a year is a way of promoting culture, of course, but it is perhaps primarily a way of bringing attention and with it a variety of economic benefits to the titular city. Visitors and the jobs that go with them are the name of the game, and ambitious targets for both are set. In the UK, the City of Culture is administered by the Department for Digital, Culture Media and Sport, the spectacularly feeble DCMS, a department which has been starved of funds and high-placed allies throughout the succession of Tory ministries recently ended, and which has been led on the whole by a long, long procession of useless placemen and placewomen hoping only to move to more senior cabinet positions. It may be worth recalling that the idea of the City of Culture was originally a European one, and indeed that a number of UK cities were booted off the shortlist when the UK left the European Union. The credit for the origination of such a scheme is usually given to Melina Mercouri, the Greek Minister of Culture of the 1980s, although I have a shapeless memory that it was also very much initially driven by Jack Lang, her French counterpart. Neither Mercouri nor Lang were place(wo)men; any contemporary UK citizen might well look with enormous envy at ministers of culture with that degree of energy, with that obvious concern for culture, and with that level of cabinet support. Lucy Frazer, anyone? She was the last of that long line of Conservative Secretaries of State for Culture (the department has gone under a series of names, including at one point being the Department for Culture, Olympics, Media and Sport, as though the Olympics were somehow not a sporting event). Ms Frazer’s achievements in the field of culture have not, as cricket commentators used to say, troubled the scorers. I don’t know how far back the planning for Bradford as the City of Culture went, although the announcement was made in May 2022 – during the tenure as Culture Secretary of Nadine Dorries – a placewoman if ever there was one. However far back we go, the Department has made over £15m available to Bradford – and that without counting substantial further funding from the Arts Council and various of the National Lottery funds. Add Bradford council’s own money and money from the region and it begins to add up. It’s small, small money in national terms, but it’s relatively big money for Bradford and for culture.

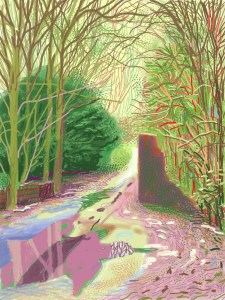

Photographed in the courtyard of Castell Coch in

Cardiff

I called Aïda Muluneh’s show a commission: it was new work made for this occasion, and it is scheduled to tour after Bradford to one city from each of the home countries. It will go to Belfast, to Cardiff and to Glasgow. The whole show is called Nationhood: Memory and Hope. It opened in Bradford in January 2025, and will close in December of this same year. Because of that nationwide tour, Muluneh sought to make pictures based on her understanding of the cities of the tour, and that’s her main series, called The Necessity of Seeing. She made brightly coloured tableaux in each of them, and those pictures directly address her knowledge and impressions of those places. In addition, she made simple black-and-white portraits of people who helped her to understand the unfamiliar British cities in which she worked. In another addition, a number of emerging portrait photographers, chosen deliberately as representing those same cities, are included in Nationhood: Memory and Hope.

All in all, I’d call that a relatively big deal. Aïda Muluneh is a very well-travelled Ethiopian artist, now based in Abidjan, in the Ivory Coast. She has lived in Yemen, studied in the United States, curated a lot in Africa. Her work is in major institutions and she has a number of considerable achievements to her name (such as curating and contributing to the exhibition accompanying the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019). I don’t know how one could sensibly rank such things, but I’d say that she is pretty high in the list of those African artists with a reputation on other continents. It was a very considerable feather in the cap of Impressions Gallery and its distinguished director Anne McNeill to be able to commission Muluneh. So then, how come there has been zero attention given to this show? I may be wrong already now, and blog pieces such as this one certainly have a habit of going out of date, so I’ll certainly be wrong later, but there has been almost no national press for this exhibition at all. I find a short notice in Creative Review, plus local notices in the Bradford Telegraph and Argus and the Yorkshire Post, with elsewhere trifling mentions as part of the general publicity noise about the opening of the City Culture on a freezing night in January. Richard Morrison in The Times liked Aïda Muluneh’s show, but he had a scant paragraph to devote to it.

Plainly, some mistakes were made. It is relatively cheap and relatively straightforward to produce a catalogue. A catalogue of Muluneh’s show would have helped to circulate the ideas in it and would have kept them current after the tour had come to an end. There is no catalogue. There is not even a complete online listing of the pictures she made. Still, many shows without catalogues garner more attention than this.

The United Kingdom is comparatively rich in broadsheet papers. Yet none of them really manage to take photography seriously. There are many reasons for that, among them the fact that vigorous and thriving review activity seems to happen only where there are major or monolithic cultural institutions pumping out what is now increasingly known as ‘content’. Major publishing houses get reviewed; so do record companies and opera-houses and theatres. But photography still remains in large part a set of overlapping cottage industries. There are some very big players : the Victoria & Albert Museum, for example, or Getty Images. But they don’t dominate their space as Random House or Covent Garden do theirs. Lots of different smaller content-producers defeats the national reviewing system.

Still, for £15m of national public spending to be led by a show by an international artist with a year-long nationwide tour and then for that show to get next to zero attention is a pretty spectacular failure not just of the reviewers and their editors, but of the legions of marketing and comms people who were available to Impressions Gallery, to Bradford, and to the national government to promote it. One can like or admire or be intrigued by Aïda Muluneh’s new British work – or not. It is certainly very intriguing to have a distinguished outsider contemplate four British towns, their history and their present. But before it can be liked or admired, it has to be seen. Muluneh has every right to feel that the work was well commissioned but not nearly well enough publicised. Not enough people have seen it yet. Here’s to hoping that when it re-opens in Belfast in June it will get a relaunch that generates the attention it merits. It was, after all, done with our money.

====

List of the other (portrait) photographers included in Nationhood: Memory and Hope

From Bradford: Roz Doherty and Shaun Connell

From Belfast: Chad Alexander

From Cardiff: Robin Chaddah-Duke and Grace Springer

From Glasgow: Miriam Ali and Haneen Hadiy