Compass Camera. Designed by Noel Pemberton Billing in England Made by LeCoultre &Cie in Switzerland

I have less of the fetishist enthusiasm in photography than many. I own no dun-coloured waistcoat with thirty pockets, for example, and I find that I cannot concentrate through (let alone contribute to) even the first bars of any conversation about anti-aliasing filters. I’ve never been a photographer; I am disbarred from the whole freemasonry of gear.

Yet that fetishism exists. Here’s a little gadget which I’d like to hold in my hands. I’d like it on my mantel. I might even put it in my pocket and rub it surreptitiously, like a worry stone or a rosary …

Compass Camera

Compass Camera

Compass Camera

I’ve succumbed, you see — most unusually for me — to a photographic object. I want to own one. And it comes as the pivot to a whole group of stories.

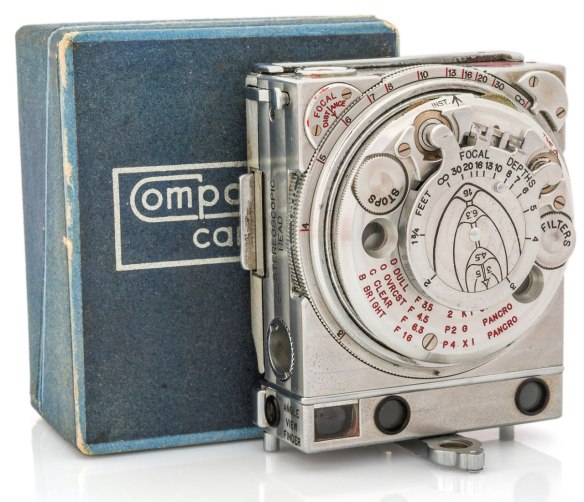

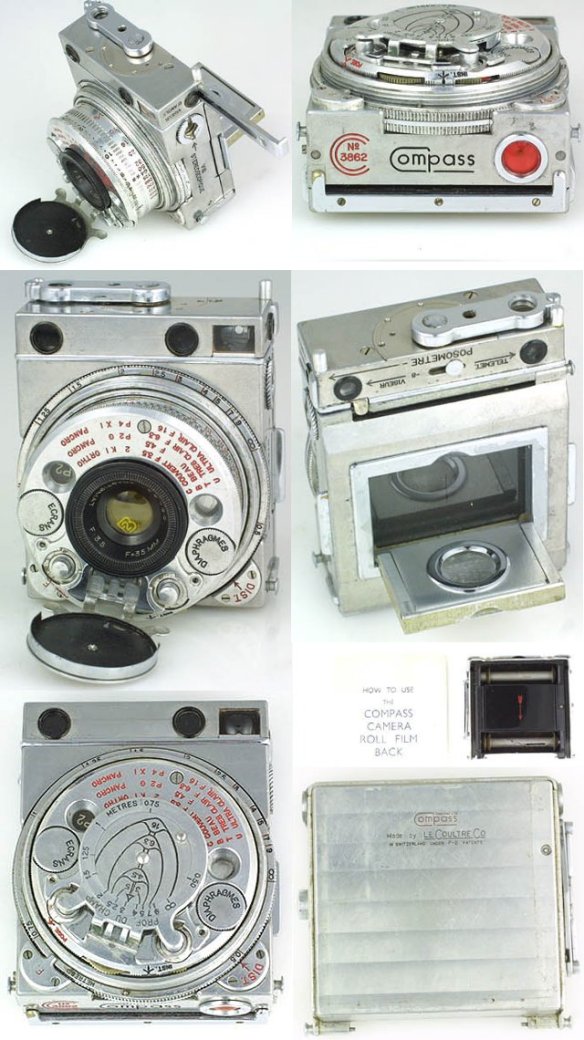

These pictures, harvested online, are of something called a Compass Camera. The pictures come from many sources, and I’m grateful to all of them, but I want to send you to just one among them. The site http://www.submin.com not only contains many detailed comparisons of different models of Compass, but also a substantial number of manuals, promotional material and so on, reproduced page by page in their entirety, an invaluable guide to the machine itself and the context in which it was offered.

The Compass is tiny – less than 3 inches square, and barely more than an inch deep when closed. It dates from 1937. It’s so intricate that it had to be manufactured by a Swiss watch maker, LeCoultre. As a feature on it in Camera magazine in 1965 put it, the Compass was ‘everything but a success.’ Part of its problem was simply the price: at launch, it cost £30, compared to the Leica selling at £15.

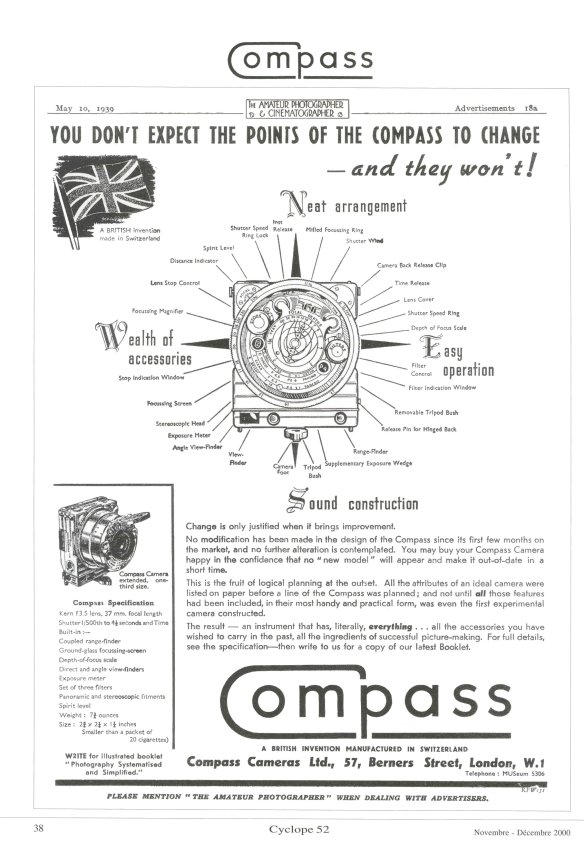

Compass advertising in Amateur Photographer, 1939, reproduced in Cyclope 52, 2000

Another difficulty would have been its phenomenal fiddliness. It looks like a fantasy of what a spy camera might be, yet you’d have to wonder what kind of spying would offer the leisure to manipulate quite so many tiny dials and switches to operate the thing. It takes 35mm film – perfectly standard stuff, you’d think, ideal for spying. Except not quite. It takes individual sheets of 35mm film, pre-backed on light-tight paper, which are loaded like the single plates of much larger, heavier (and acknowledgedly slow) cameras. A later modification allowed use of a roll of film, but even that was hardly convenient, as it was limited to six exposures. Yet some 4000 of these things were made; some of the design ideas it encompassed are still in use. It was brilliant, it worked, and it’s beautiful.

Compass in the Hand, from Amateur Photographer, 1943

Compass Camera

Compass Camera

Compass Camera

Compass Camera

Compass Camera

Compass Camera. Designed by Noel Pemberton Billing in England. Made by LeCoultre & Cie. in Switzerland

The Compass was the design of a man called Noel Pemberton Billing, about whom fact and false fact swirl. If this little camera is beautiful, his more abstract ideas were vile.

Michael Pritchard, in whose History of Photography in 50 Cameras I first met Billing, calls him mildly enough “a true English eccentric”. The historian G. R. Searle (who also wrote Billing’s entry in the Dictionary of National Biography) was more outspoken. As quoted by Lucy Bland (in Modern Women on Trial: Sexual Transgression in the Age of the Flapper), he called Billing “the most conspicuous and dangerous of all the war-time jingo demagogues”.

Billing was an engineer and designer, principally in aviation. He held hundreds of patents, including many to do with cameras, but stretching beyond them as far as a simple package for safety razor blades. He designed improvements to the gramophone player, too. Philip Hoare, in an essay called I Love a Man in Uniform: the Dandy Esprit de Corps, calls Billing “an Edwardian Lothario, the inventor of the seaplane”.

“Like the prewar ‘nut’, but decidedly more virile,” he goes on, “this dandy autofact’s accessory was the car: Billing drove a lemon yellow Rolls Royce and other, futuristic motors of his own invention; commentators noted that he dressed in ‘unusual clothes,’ especially long collared shirts worn ‘without the usual accompaniment of a necktie’.”

Hoare tells us – with a picture from his own collection to back it up – that Billing “had a ledge of flesh inserted in his cheek to keep his monocle in place”.

Had Billing stuck to aviation, he might have been a solid success. He was in it from the very first, experimenting with gliders almost as soon as he came back (in 1903) from a youthful fugue to South Africa. (He had joined the South African police and seems to have served for a while in the Second Boer War.) Billing opened in 1908 what was probably the first airfield in England, on a marsh in Essex. It was overtaken by Goodwood as the centre for pioneering flight. He started an early aviation magazine, Aerocraft in 1909. He raced cars (and also steam yachts). He tinkered. He had money, and he also made some. In 1913, he made a £500 bet with the aircraft engineer Frederick Handley Page that he could get his flying licence from scratch in twelve hours of flying. He had probably been practising for months or years before that; he was that kind of man.

But he won his bet, and the winnings (a very substantial sum at the time) allowed him to invest in his very own aircraft factory. He put it on the Solent, on the River Itchen, in fact, because he wanted to specialise in seaplanes. He designed original configurations of aircraft, including one with four stacked wings. He was interested in planes to hunt down Zeppelins, he thought about planes which could land on water and ditch their wings to become lifeboats for damaged ships. None of this was nonsense: the whole industry was full of trial-and-error, chimera-chasing, making-do. It was wartime, and aviation was an industry whose boundaries nobody knew. Pemberton Billing got close; but never quite got the cigar. When the government effectively bought out his plant, it survived by repairing planes damaged in the appalling carnage of the time. Never mind the enemy, these things fell out of the sky with alarming frequency and terrifying consequences. He was really close, though. The telegraphic name of the Pemberton-Billing company, chosen by Billing as the superior opposite of submarine, was ‘Supermarine’, which became the company name and which would echo in aviation glory as the maker of the Spitfire – but only after he had sold his share.

Pemberton-Billing PB1, as exhibited at the Olympia Aero Show, London, March 1914. One 50hp Gnome seven cylinder rotary engine. Span 30ft. Length approx 27ft. Maximum speed 50mph.

Billing retired from the Royal Naval Air Service after serving only briefly. He wanted to make a name in politics.

The issue of Flight (“official organ of the Royal Aero Club of the United Kingdom”) of January 13th 1916 contains the announcement of Billing’s convenient eleventh-hour promotion to Temporary Squadron Commander at the same time as the notice of his resignation from the Service. The issue runs what is in effect a campaign manifesto for Billing, including a front-page editorial, a full-page portrait, and a long and frankly hagiographic profile.

“His object is to become the advocate in Parliament for the very extended air policy which has been so strongly urged in the past in ‘Flight’…From his knowledge of aviation he is not likely to be led astray by a lot of flap-doodle statements emanating from those who have some axe to grind of their own.”

Pemberton-Billing as a Lobbyist for Aviation

Tellingly, Billing is described as standing for parliament ‘at the request of an influential committee’.

In other words, he was backed as a lobbyist. He was eventually elected, in Hertfordshire. Partly because he was loud and a showman, and partly because the arguments for increased air power were in fact sensible at a time of appalling slaughter on the ground, he acquired a certain populist renown.

Then things went from the zany Buster Keaton world of early aviation to something a great deal nastier.

With the financial backing of Lord Beaverbrook, Billing opened a journal called The Imperialist (renamed in early 1918, in case anyone had any doubts of its methods, The Vigilante). Openly anti-Semitic and homophobic, this looked for people to blame for the way the war was going. Billing was persuaded that a secret German campaign called The Unseen Hand was sapping the British will to fight. And what was The Unseen Hand? Networks of prostitutes, deliberately infecting our boys.

“The German, through his efficient and clever agent, the Ashkenazim, has complete control of the White Slave Traffic. Germany has found that diseased women cause more casualties than bullets. Controlled by their Jew-agents, Germany maintains in Britain a self-supporting – even profit-making – army of prostitutes which put more men out of action than does their army of soldiers.”

In December 1917, Billing ran an article by the virulently anti-Semitic Arnold Henry White saying that Germany had a network of homosexual agents (he used the word urnings) on the same kind of mission.

“Espionage is punished by death at the Tower of London, but there is a form of invasion which is as deadly as espionage: the systematic seduction of young British soldiers by the German urnings and their agents… Failure to intern all Germans is due to the invisible hand that protects urnings of enemy race… When the blond beast is an urning, he commands the urnings in other lands. They are moles. They burrow. They plot. They are hardest at work when they are most silent. Britain is only safe when her statesmen are family men.”

Then a Black Book appeared (although mysteriously, its appearance seemed always just around the corner). The book was in the hands of a German aristocrat, briefly king of Albania. Then it was in the Home Office… Such a one had seen it but couldn’t produce it just now. The Black Book was supposed to be

“a book compiled by the Secret Service from the reports of German agents who have infested this country for the past 20 years, agents so vile and spreading debauchery of such a lasciviousness as only German minds could conceive and German bodies execute…. for the propagation of evils which all decent men thought had perished in Sodom and Lesbia…. the names of 47,000 English men and women…. Privy Counsellors, youths of the chorus, wives of Cabinet Ministers, dancing girls, even Cabinet Ministers themselves, while diplomats, poets, bankers, editors, newspaper proprietors and members of His Majesty’s household follow each other with no order of precedence…. Wives of men in supreme positions were entangled…. In lesbian ecstasy the most sacred secrets of State were betrayed.”

This kind of stuff was barely coded at all. Readers would have recognised, I think, in the “wives of men in supreme positions” an allusion to Margot Asquith, wife of the recently unseated Prime Minister, and a constant lightning-rod for gossip and slander. The reference to ‘dancing girls’ would certainly have suggested Maud Allan, the most famous dancing girl of the time. The vision was clear – if clearly mad. There were 47,000 high-placed names, all homosexual, all capable of being blackmailed by Germany.

On it went. The kind of stuff that only a semi-hysterical population can take seriously. But the war looked very hard to win, to say the least. Passchendaele had petered out only recently – the ‘end’ of the battle is usually given as November 1917. In the face of consistently dreadful war news, hysteria was more understandable – and more exploitable – than at more stable times.

Billing went further and further. He claimed that Jews in government were conspiring in treason to lose the war; he fomented a series of attacks on Jewish businesses or even on those of people with German-sounding names – all very nasty, and an obvious prefiguring of the habits of British fascists to come.

No need to be a psychologist to see that Billing was a fantasist, or even to suspect that he may have had some trouble dealing with an element of homosexuality of his own. He was certainly an extremist of the right-wing, of the kind that is violently anti-everything. The cast of characters that whirled around him is ‘colourful’ but also included deeply dangerous people. Lord Beaverbrook I’ve mentioned as one of his sponsors. He was the man of whom Evelyn Waugh said “Of course I believe in the devil. How else could I explain Lord Beaverbrook?”. Billing was involved with Charles Repington, the military correspondent of The Times (and later the Morning Post), a sinister military figure openly contemptuous of politicians and privily plotting against them when their views on strategy differed from his own. Billing employed on The Imperialist the certifiably mad American Harold Spencer (discharged from the British Army for paranoid delusional insanity), the author of a shrilly anti-Semitic book published in 1918 under the title Democracy or Shylocracy.

In early 1918, a private performance was planned of Oscar Wilde’s Salome. It had to be private because the theatre in England was carefully censored (as it remained well into the 1960s). Salome was to be played by Maud Allan, the American actress. The Vigilante published (under the screaming title The Cult of the Clitoris) a hysterical claim that the thousand people due to attend the performance would all also appear in the Black Book. Maud Allan sued Pemberton Billing for criminal libel for suggesting that she was a lesbian. The trial was a sensation: mud of every kind was flung. The court became the perfect launchpad for Pemberton Billing to air his conspiracy theories. A succession of witnesses made spectacular allegations. Dr. Cook, tuberculosis officer for Lambeth, gave evidence to the effect that everybody concerned in the production must have perverted minds, be sadists and sodomists.

Maud Allan as Salome – Photo Reutlinger

As always around Billing, the cast of characters was gaudy. Ms. Allan was herself a sensation. She was a huge star, having long been performing as a dancer to big audiences in London in costumes quite amazingly revealing for the date; but she was also revealed to be the sister of a man executed in California in 1898 for the lurid murder of two women. Oscar Wilde’s former lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, now a vehement homophobe, gave evidence, as did an extraordinary woman called Eileen Villiers-Stuart.

“Lloyd George and his advisers,” according to Toni Bentley in Sisters of Salome, “hired a young woman with some experience in political subterfuge, as an agent-provocateur. She was to offer Pemberton-Billing her support, information, and sexual favours if necessary, and then lure him to a male brothel to be secretly photographed for blackmail. Eileen Villiers-Stuart was a political adventuress primed for the job. She was an attractive, twenty-five-year-old bigamist, and her lunch with the Independent M.P. was all too successful. By the end of the afternoon, mesmerized by him, she flipped her allegiance, slept with him, and divulged the Liberals’ conspiracy to blackmail him. She even agreed to testify as a star witness in her new lover’s libel case.”

Gaudy is the word. These people didn’t care too much about telling the truth. Spencer and Villiers-Stuart both later admitted to having lied in court. The judge, Charles Darling, a very senior figure, barely kept control of the trial, but in June 1918 Pemberton Billing was acquitted of all charges of libel. For a few days there was uproar; it seemed a vindication of his preposterous views. The fascination of the case has not diminished over time. It is, for example, one of the events rumbling in the background of The Eye in the Door, the second of Pat Barker’s novels in the Regeneration trilogy. No doubt you could make a movie of the life of Noel Pemberton Billing.

The uproar got Billing re-elected to Parliament, but as the credibility of his witnesses became harder to maintain, and as the victory in the war removed the primary cause of the public hysteria in which Billing’s theories had found their ground, he gained little traction from the case. He retired from politics in 1921.

One of the points of the Compass is that it was meant to be a complete camera system: everything you might need was designed into the little block of machined aluminium, including filters and other such elements normally carried separately. Even the tripod was beautifully designed and made for it. A swivelling connector between camera and tripod was built in to allow matched pairs of stereoscopic pictures to be made without effort. Another connector with five notches allowed perfectly aligned panoramas. There were choices of methods of focus, careful exposure ratios (calculated in Compass Units, which were engraved on the machine). It even had a spirit level built in. If you really were in a hurry, there was a SNAP setting in the middle of the shutter speeds (although even getting to that was fiddly).

It was maybe too perfect. Small wonder it was made by a watchmaker. It had some 250 parts. To take a picture with such a thing involved daintiness and precision at the expense of convenience. Pemberton Billing designed another camera in 1946 – the Phantom, which never went into production. It was Michael Pritchard, then at Christie’s, who was responsible for the sale of the prototype in 2001. It was estimated at £8,000-12,000 and sold for £146,750 – smashing the auction record for cameras at the time. Pemberton Billing should have stuck to what he knew; he was a really good designer.

Compass Camera

Compass Camera

Compass on its tripod

Compass Camera

If you haven’t seen quite enough pictures of the fetish-object yet, there’s an amazing little film in which somebody called Sarah Smoots carefully .. fondles a Compass camera for quarter of an hour. That should probably be enough.

What an extraordinary story of a clearly paranoid-obsessive character an equally passive-aggressive camera! Hats off to your research, as always.

LikeLike

Thank you. But I’ve done no more here than cobble together a report of the research of many others, some of whom are respectfully named in the piece. The story has been known a long time; I’m merely giving it some air.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What you call cobbling is actually rather fine embroidery!

LikeLike

quite remarkable engineering, I did in fact have the pleasure of holding one briefly from one of my collectors in Tokyo, had no idea what profoundly twisted views came from its designer. Eloquent as always Francis.

I do wonder when you may consider my 32 years of large format analogue practice exploring water as a primary medium. Today as in the past we fight battles over access to oil, soon those same wars will erupt over humanities hunger for clean water. This, the great fate of humanity consumes my thoughts daily. Continuing to explore it’s environmental signature is a conversation that I have made a lifelong commitment to; that of unencumbered fresh water to all living species, and, clean oceans enabling their vital ecosystems to thrive; right now across vast areas around the globe they are barely surviving.

with gratitude

Alexander James Hamilton

LikeLike