As you take the Docklands Light Railway back to London from David Bailey’s new exhibition it is all too easy to fall into pools of irony as deep and as dank as the great docks themselves. Bailey was born in Leytonstone, in the east of London. As he once put it, “we were posh East End, if that’s possible, but I had cardboard in my shoes and was at the bottom of this cheap private school; some of the parents had tobacconists’ shops, which was a bit posher.” London seen from the DLR is a wasteland. It wasn’t wrecked only by the bombs; they didn’t help, but they were only one element in an ungodly soup of unfettered industrial development in the early days, abysmal social housing and forced movements of people, the dock strike, the late unlamented Docklands Development Corporation, incompetent and venal borough government… The Olympics, without which there would certainly have been no exhibition here, are touted as providing ‘regeneration’ and perhaps to a minuscule extent they do. But an awful lot of lipstick has been applied to sows in the name of the Olympics, and precious few of them will look any better when it wears off.

David Bailey has an OBE, but I wonder if he turned down a knighthood at some time in the past? It would be just like him. But we should offer him one anyway. Now well into his seventies, and still as passionate about photography as he ever was, Bailey has upped his game again to produce a top-notch exhibition in a former Compressor House on a blighted bit of dockside in the former Royal Docks.

I asked Bailey what used to be compressed there, and he answered off-hand, meat from Argentina. I had visions of corned beef squashed into cans. It turns out not to be quite right: it’s a big building, but it housed just the refrigeration plant. There used to be a pond on the roof to hold the water needed to circulate through the machinery. The meat from Argentina was in literally acres of cooled sheds which no longer stand next door. It’s curiously typical of Bailey that he knew the answer, but not precisely. He’s a considerable scholar, and a technician of the highest order. He’s meticulous about cameras and film, but he’s also impulsive and imaginative and blessed with the most astonishing reflexes.

Bailey’s exhibition takes place under the umbrella of the ‘cultural Olympiad’ with a view to leaving a cultural legacy in Newham (a particularly blighted East London borough). It was ‘produced’ by something called Create – principal sponsor, the Deutsche Bank – and the Arts Council are claiming a piece of the action, too. It would be interesting to see the real books for this farrago. It is all too easy to imagine how much less the productions of the ‘cultural Olympiad’ will have done for their putative clients than for the armies of arts administrators and other employees who have been on good or very good salaries in their name. Bailey claimed to me that he was out of pocket for the show, and I’m sure that he is, although whether that includes abstractions such as his time freely given while he spent months in the darkroom making brilliant black and white prints I have no means of telling. But I suspect from something else that he said that he had to pay for the frames. If he did, what does that say about the level of help from the Deutsche Bank? The same Deutsche Bank whose world class art collection certainly doesn’t go short of a few frames?

It is an exhibition of brilliant photography, no doubt about that at all, wide ranging and varied in both subject-matter and style, and sharp as Cockney banter for tone. It is so rich in types of photography for which Bailey has been less known – magazine-style reportage stories, topographical views, contemporary street photography – that it rewrites his reputation at a stroke. Bailey used to be known for portraits of celebrities, for horny fashion photography, and for commercial videos. Now, in his seventies, he looks much more like an acute and anxious social commentator.

Newham residents get in to Bailey’s show for free. No scope for irony there: that’s good. If one of them eventually becomes a photographer or a social scientist or a fashion maven as a result of an impetus originally found in front of a picture of the Kray twins seen in the former Compressor House of the refrigerator for the meat sheds of the Royal Albert Dock, that will be a tangible ‘Olympic legacy’.

As a matter of fact, I got in for free, too. I’m a critic and the publicity machine for ‘cultural regeneration’ needs the press. I may therefore represent a tiny irony among others. But the big ironies are there, too. As you reach the elevated sections of that ride away, on the train that was meant to be the principal infrastructure investment for the entire East London region, you see the shining towers of the cities of the plain, the Sodom of the Isle of Dogs and the Gomorrah of the City of London. You see them above a blightscape of cheap industrial units scattered around the original low-lying marshland. Bailey’s show is on the other side of the same huge dock as the City Airport. Not a single sea-going vessel is in there, not one, in what used to be one of the busy ports of the world. On the dockside, a piece of international-crap architecture, a Newham prayer for attention from the incoming jets, stands ready to be rented to corporations who just aren’t coming. It’s within a couple of miles from those great financial centres, yet there’s nothing. The people who work at the tops of those towers get their free papers from air lounges, not from among those abandoned on the seats of the Docklands Light Railway.

A framed black and white portrait hangs in a hallway. Two children, familiar. The little girl is hooting with laughter, the little boy solemn. The colours of the hallway are muted, the colours of old Land Rovers, army surplus colours. A cheap paper dado rail divides the lower grey-blue (harder wearing, vaguely institutional, shows the dirt less) from the custardy cream above (futile attempt to reflect more light). The furniture is cheap, the light bulb such a weak orange it’s almost brown. Austerity Britain in a passageway. Then recognition: those children are Princess Anne and Prince Charles. And a final clue in the caption: the hallway is in the Krays’ gambling club. Remember that TV sketch in which John Cleese, Ronnie Barker and Ronnie Corbett stood in a line of diminishing height and explained about class? You can find it on YouTube. Bailey is like that at best: pleasantly witty but hard and true and cutting underneath. And we never really knew. Here’s a portrait of an East End lady drinking a beer. It’s in colour, but it comes straight from Bill Brandt. More than that: it has the social sharpness of Martin Parr long before Parr himself. This is a London that we’ve been asked to forget. But Bailey hasn’t forgotten.

In Paris, Atget used to photograph in what was called la Zone, the area cleared of housing just outside the city wall to make a field of fire. Who was intended to be aimed at is not always so clear: it might have been the Germans after 1870; or it might (at exactly the same time) have been working Parisians after the Commune. La Zone, by the time Atget came to it, was repopulated by unofficial Paris: shanty construction, dubious trades. East London looks like la Zone, and feels like it, too. There is meant to be a new city in all this, yet to rise very far, which is Stratford, the city reborn of the Olympics. It has a large shopping centre to which people come from far and wide, to buy consumer goods with their borrowed money. The new symbol of Stratford may be the worst-conceived monument ever built in London, the gnarled knot of the ArcelorMittal tower. It’s an insane postmodernist joke, a piece of self-flagellation. It’s meant to be a brand new Eiffel tower for the Olympic park. The Eiffel tower was built for a trade fair, too, and it, too, was widely disliked at the outset. But the Eiffel tower remains stiff and proud and nothing in Paris can be built to obscure the lines of sight to it now. The Stratford tower is an Eiffel tower with brewer’s droop. It’s hard to know whether to applaud the optimism of the people who believe in the regenerative power of the Olympics, or whether to curse their naivety.

Marc Reisner wrote in the mid-1980s a searing book called Cadillac Desert, about the great US irrigation projects. He shows huge public investment in making water available in areas of the Western United States that are essentially dry was transformed into profit for private corporations. The scale of state investment was prodigious. It was a real Socialist enterprise: bringing water to Southern California almost drained the Colorado River dry. And the beneficiaries? Citrus growers. It’s the story of the film Chinatown, in which the corruption is on such a huge scale that it’s hard to see it from close up. I wonder if the same will not in the end prove to be true of the great ‘regeneration’ projects. How different will Newham really be, once the great Olympic circus has moved out of town?

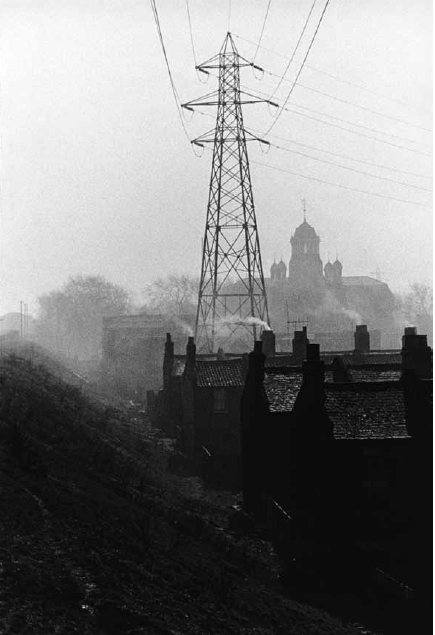

Bailey knows all this. His exhibition is anything but naïve. The cumulative view of the East End that he provides is one of loss, not gain. In one picture, Abbey Mills Pumping Station, the pivot point of Bazalgette’s great north London sewage network, is given a kind of smokey glory of a Eugene Smith kind.

Abbey Mills probably quite literally saved London. Without it, London was drowning in its own shit. A huge and ambitious piece of underground engineering pumped the effluent away and one or two glorious buildings – Crossness south of the river, Abbey Mills to the North – marked the achievement. Abbey Mills, built in a splendid Victorian Byzantine style, used to have four huge minarets at its corners, but they were taken down as making it too easy for the Luftwaffe to steer by. Abbey Mils, Bailey seems to be saying, that was then; when capital contributed to cities. Further along, a picture of a cheap blue hoarding.

It blocks out the sky. It’s brighter than the sky. I don’t think it’s actually the infamous Blue Wall that locked Londoners out of the Olympic site and divided the places that would receive fancy new terrazzo surfaces from those condemned to remain in London Stock and Engineers’ Blue. This one is just a hoarding, I think, peeling. Behind it, rivetted water tanks wait to be dismantled next time the price of scrap metal goes high enough to justify it. This is now. Inadequate investment, and profit made only from money spent long ago.

A sylvan river? A rural cottage? Stratford and Stepney Green respectively. Is Bailey laughing at the culture of the glamorous holiday, the city break, the Maldives and the Seychelles? You didn’t get them when you came from Leytonstone. Or is he more plainly simply showing us that cities are never just concrete and steel?

Some of the portraits in the show are pure Bill Brandt. A craggy drinker in a pub waves his pint high above us. It’s close to the camera, so is bigger than his head. In his other hand, at the diagonally opposite corner of the picture, his roll-up, still in pieces. Both pint and fag are expertly clutched without spillage. His hair is floppily long, not because of fashion but because it costs money to get it cut. He is of the generation that used to do even rough work in a suit: an older man behind is still in working tweed, although the hero of the picture is in some kind of decommissioned double-breasted number. I even wonder if it might not be a demob suit, almost the only thanks you got for leaving the Army at the end of the war. This picture dates from 1968, so the suit would be twenty years old if it were so, a goodish time for a suit to come down in the world. He wears a tightly knotted but not very ironed scarf around his neck, and instead of a waistcoat a brown knitted cardigan, open. He reminds me of something, but it takes me a while to place it: if he had only the wide leather belt, he would look for all the world like a member of one of the greatest of all the industrial tribes, the canal navigators.

The great boom in canal building was in the 1790s, a generation before photography. There are pictures of the canal men, though, because habits changed slowly as long the canals still functioned properly. Eric de Maré was a prince among canal photographers, and the RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects) gave him a long-overdue show not that long ago. Somehow Bailey seems to have read that old industrial heritage in this one man waving his pint at the camera; it’s a million miles from the other Sixties that Bailey was working at the same time. In Carnaby Street, Bailey was making a world, or helping to. In the East End, he was trying to understand the one it was replacing.

There’s great beauty in Bailey’s view of the despoliation process: he prints black and white like a silversmith chases metal. A woman in profile – headscarf and fag – in front of a wall of price tags is fully worth its predecessors by Walker Evans.

By the time he gets to working fast in the street with digital equipment and in colour, he finds beauty another way. A woman in a wheelchair (with a stack of Blockbuster videos hung in a bag from the handles) passes a woman in a shalwar kameez. Neither acknowledges the other, but the earthy solidity of the textiles of the wheelchair rider is pointedly contrasted against the gossamer translucence of the floating drapery. Just in case you didn’t get it first time, a lens flare acts as a miniature point of starlight. “Shh ! “, this picture says, as our grandmothers used to, “in that silence an angel passed”. In an older picture, a curiously cartoony doorway somewhere like Bethnal Green has white paint daubed next to it. So do all the other doors in the street. Lot 13. It’s an auction. Winner takes the whole street.

What to make of a show like this?

One, that the stories that Bailey has to tell are different to but no less substantial than the fashion and portraiture from which he made his name. This is a sustained and highly successful exposition of the lack of care that has been found acceptable for a substantial swathe of London and for the people who live there. The Krays are in the show, brilliantly photographed. They’re the only gangsters named, but they’re not the only gangsters present.

Two, that David Bailey has had insufficient attention. That sounds absurd. One of the most famous photographers we have? Certainly, but he’s almost never had a public show – one big one at the Barbican (and the Barbican is oddly funded, it’s not really a national venue) otherwise scraps. It is impossible to imagine a German photographer of equivalent status, a French or a Dutch, to have received so little public confirmation. Our curators really haven’t been doing their work if Bailey can unearth treasures on this scale in a few months of trawling his own files. There’s colour work here of spellbinding subtlety and control, as well as the glorious silver printing. As a little bonus, there’s a wonderful early self-portrait of Bailey as a mod, surrounded by jazz instruments.

Lots of people won’t go to this show because it’s far out on the Docklands Light Railway; well, it’s there for good reasons. And one of those reasons is that Bailey sees to it that – for any viewer with eyes in his head – the trip back will be freighted with irony.

One final footnote. I see that the show is dedicated to the late Claire de Rouen, bookseller of the Charing Cross Road, and a person whose enthusiasm for photography was the engine for an entire generation of UK practitioners. It’s an elegant gesture of Bailey’s to lift his hat to her in that way.

Really enjoyed this analysis, and it’s really helped in the writing of an essay on David Bailey’s East End. Thanks! :)

LikeLike

Pingback: Getting Bailey « >Re: PHOTO

I hugely appreciated reading your analysis of the images and Bailey’s work. I got to your site after wathching a documentary about Bailey on TV this evening.

LikeLike

….oh and also the photo of the Kray’s club with a portrait of Charles and Anne reminds me of Mr Bridger’s prison cell in The Italian Job. Now back to work.

LikeLike

Have stumbled upon this page while researching The London Docks in the 60’s. As with all procrastinating writers, I became distracted and read this article. The floppy haired man is possibly a docker. He reminds me of my dad. Is there a book of the exhibition do you know? A great read with thought provoking photos.

LikeLike

I don’t think there was a book of that particular exhibition. Lots of good books of David Bailey’s pictures, though.

LikeLike

Yes there is a book. It’s a slim, large size, cardboard bound catalogue and it’s beautifully printed. I bought one from the William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow for £15.

LikeLike

Pingback: The week that was: 2-8 July « Camera Portraits