A striking group of photographs comes up for sale next week which merits wider attention than it is likely to get.

John Beasley Greene (1832 – 1856) was an American archaeologist based in Paris. As a glance at his dates will show, he died shockingly young, yet not before leaving a quite remarkable body of work. The website of the Getty Museum furnishes this simple information:

“In 1853 at the age of nineteen, Greene embarked on an expedition to Egypt and Nubia to photograph the land and document the monuments and their inscriptions. Upon his return, Louis Désiré Blanquart-Evrard published an album of ninety-four of these photographs. Greene returned to Egypt the following year to photograph and to excavate at Medinet-Habu in Upper Egypt, the site of the mortuary temple built by Ramses III. In 1855 he published his photographs of the excavation there. The following year, Greene died in Egypt, perhaps of tuberculosis, and his negatives were given to his friend, fellow Egyptologist and photographer Théodule Devéria.”

That is why they survived; indeed they are housed today in the Devéria papers at the Musée d’Orsay. Greene had been a pupil of Gustave le Gray, and was one of the founding members of the Société Française de Photographie. His imagery is peculiarly far from that of Gustave le Gray, however, and even farther from that of the more famous French orientalist photographer Maxime du Camp.

For du Camp, at least, if not for Le Gray (who settled in Cairo and lived there some twenty years), travelling in the East was an unashamedly colonial venture. Du Camp’s famous journey in the company of Gustave Flaubert had brought back astonishing photographs of Egypt, but an Egypt empty of modern life, a kind of moonscape with no farming, no trade, almost no people at all. This was a kind of empty treasury, and the implication was that it was ripe for take-over by a (supposedly) benevolent and enlightened West. The principal recurring figure in du Camp’s Egyptian pictures is that of his servant, the Nubian sailor Hadji-Ishmael., used by du Camp to give a scale. “I told him,” du Camp recollected later, “that the brass tube of the lens of the camera was a cannon, that would vomit a hail of shot if he had the misfortune to move.” The figure sitting on top of the colossus at Abu Simbel in du Camp’s famous view entitled ‘Ibsamboul. Colosse Occidental du Spéos de Phré’ is Hadji-Ishmael. Unsurprisingly, given that he’s perched several feet in the air and convinced that one move would have him shot, he’s very, very still.

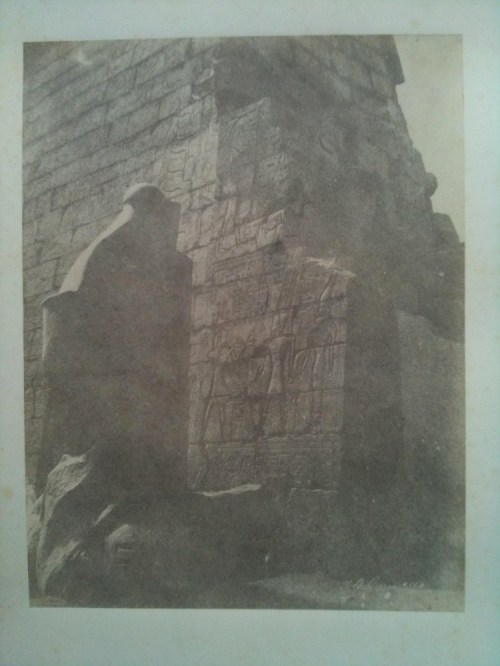

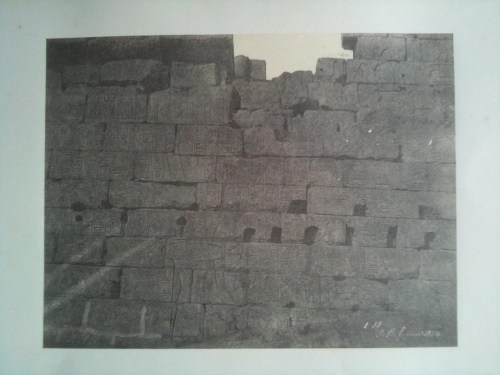

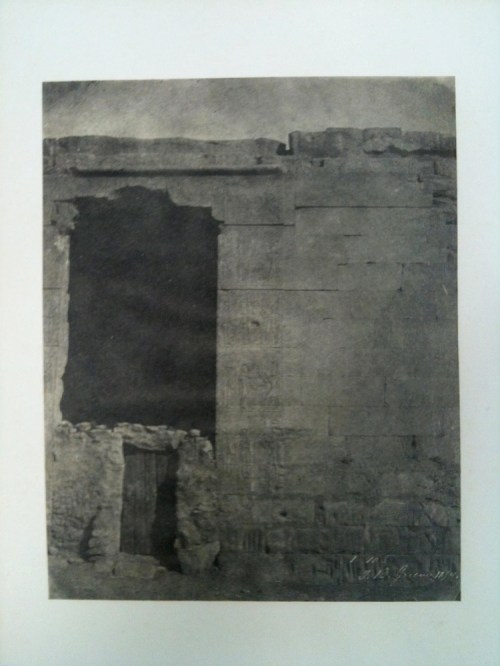

Greene was not like that. If du Camp’s more famous pictures look a little bit like the due diligence that’s done before a take over, a careful catalogue of the good things to be had in the next move, Greene’s are much more unashamedly gob-smacked. He made a famous picture of the back of a giant sculpture, for example, a beautiful study in poise and form, a romantic gesture of which du Camp would have been quite incapable. The group coming up for sale now is of studies of inscriptions. They probably came from a ‘properly’ scholarly impulse, but they’re photographed with a kind of sensuous delight in the actual textures of the walls upon which the inscriptions are found, the sand and gravel at their feet, and above all the light that shone in Egypt as no light ever shone in northern Europe. Several of them have elegant escape hatches, where a fallen panel of wall allows us to see the sky beyond. One splendid one ( Lot 139 ) has the exact opposite, a lush dark entryway where perhaps a carved panel had fallen or been stolen, above a cruddy rough wooden door. One can almost feel Greene running his hands along these surfaces and wondering how he could hope to imitate them.

Greene worked in his brief career in other modes: he made a broad view of the Nile of such astonishing peace and poise that I’ve never met anyone who has seen it and then forgotten it. But these intimate, tactile studies of beautiful remains, uncomprehending and yet respectful and desperate to learn, are among the great high points of early travel photography. It’s too easy to lump all Orientalist photographs together, too easy to be frightened of calotypes (which these are). Sure enough, the photography of the mid nineteenth century is far from us now. The attitudes which led to it are long changed, and so are the techniques which made it so horribly difficult to achieve and at the same time so magnificent when they worked. But precisely because he photographed as a sensualist first, and a scholar only after that, Greene’s eye is much closer to our own day than at first appears. Compare Greene’s Egypt to the marvellous pictures made there recently by Vera Lutter, for example, and you have a much closer family resemblance than you might expect.

The normal thing would be for these pictures to be bought by a dealer, and to sell again later to a specialist early-photography institution or collector, to be well looked after within the cloistered world of those who already know that they care. This time, I hope not. I hope these will be bought by a modern or contemporary art collector, and displayed with all the panache they deserve. It would be a mistake to think of these simply as Egyptology on paper. They are a love affair with stone, as great in their way as Monet’s studies of Rouen cathedral.

The sale is of Books, Manuscripts and Orientalist photographs, to take place at the Salle Drouot in Paris, under the auspices of the Commissaires-Priseurs Gros & Delettrez. Mr. Antoine Romand is the expert in charge.

The sale will take place on 23rd June 2011 at 14.30, and the John Beasley Green lots are numbered 135-139. The catalogue is HERE

I ought to remark that I have no connection with this sale.

This reminds me of the book ‘The Pleasure of Ruins’. Assume there’s no connection though. We used the book as inspiration for something we published on cycling in the Mountains – separating the images from the text so as not to compromise either… (sounds familiar?).

LikeLike