Marcus Coates is one of those British artists so far over the border of eccentricity that it has sometimes been hard to take him seriously. He practises a form of shamanism which enables him, by communicating with the animal world, to arrive at radically new perspectives on the human. Here is a simple listed description of his costume for a shamanistic consultation in Stavanger in 2006: “Suit (1940’s), dance rattles, brogues, red deer, prescription glasses with clip on shades” . The red deer is worn on the head, by the way, and dance rattles (in case you asked) are sets of key blanks on key rings. They look like bunches of keys, except that they don’t open anything. They’re keys for the dispossessed, and no doubt they do rattle nicely if you dance while waving them about.

It is easy to poke fun at this stuff, and no doubt many do so on a regular basis. Sometimes Coates plainly goes too far: a recent piece was a stack of scaffold boards of different lengths, which were supposed to have acquired significance because they corresponded to the wingspans of several species of albatross. This is absurd. There’s nothing there, neither emotional, nor intellectual and not even really in aesthetics. But Coates doesn’t care. As he sees it, his performances as a kind of medium communicating with the animal world will elicit interesting questions from onlookers whether they believe in what he’s doing or not. And he is not merely doing it as an abstraction, protected by the security of gallery walls. Coates has, for example, been known to put animal skins on his head in order to help the residents of a blighted South London housing estate on which his father had worked a number of years before.

I surprised myself by finding that a piece of Coates’ was one of those I liked most of all at Frieze. I’ve waited a number of days, and my intrigue has not turned into indifference and nor has the excitement of the piece diminished in memory. Coates was represented at his gallery, Kate MacGarry’s stand in Regent’s Park, by a simple grid of self-portraits. Sequences and series and grids were absolutely the flavour of the month for photographs at Frieze (I might write a piece about that if I ever get around to it), so I was quite ready to shrug and pass on. But Coates’ grid is a big success.

It consists of vertical (portrait format) pictures each about the size of an A4 sheet arranged in a rectangular grid six wide by four high. The repeat is formulaic to the extent that camera position, lighting and so on do not vary from frame to frame. And what is depicted is just the head of the artist, smeared in shaving foam. That, inevitably, is mainly white, so the background is dark. It’s called British Moths, 2011, and it’s far, far bigger than the sum of its parts.

The part of the work which is specifically Coatesian is that each portrait is given the name of a species of moth found in the UK. These titles may or may not add a layer of significance: you may find that the portrait entitled Drinker Moth (Philudoria potatoria) has a Hogarthian feel or that the Delicate Moth (Mythimna vitellina) shows a particularly lacy configuration of shaving foam, but I don’t and I forgot the names of the species as soon as I’d read them.

What is much more exciting is the way the shaving foam blurs the contours of the face and in so doing points us towards a common reading of portraits that is not very often acknowledged. Marcus Coates’ shaving foam takes us right back to the very early days of photography.

When you leaf through a magazine and a portrait of a stranger impels you to say “Oh, I don’t like the look of him”, you are making assumptions about the person based solely on your reading of a face. There is an often quoted bon mot usually attributed to Camus that “after forty,” (or thirty – I’ve seen both given with confidence) “a man is responsible for his own face”. Yet a face tells us almost nothing about the character who inhabits it. We all habitually think that we can adduce concrete certainty about the inner person from the factual map of the outside. This is a residue of phrenology, a Victorian science which boomed just before photography.

The root ideas of phrenology are not necessarily entirely wrong. Nobody I think today disputes that certain attributes of personality and of behaviour are situated in certain parts of the brain. Phrenology was the science which said that there were conclusions to be drawn about the type of a character from the shapes of the various parts of his brain visible from the outside on the surface of the skull. It formed a part of that congeries of ideas which can loosely be called physiognomy. These were much more important in Victorian art than is sometimes acknowledged: certainly a detailed description of a face in Balzac is not just a matter of features. It’s a decided map of character, too. These kinds of ideas survived a surprisingly long time. I remember for example the peculiar insistence with which the right wing writer John Buchan described one of his villains as having ‘hooded eyes’. I’m not sure it was a specifically anti-Semitic hint, but it was certainly an invitation to distrust someone on grounds of physical characteristics which objectively meant nothing at all. Some aspects of these ideas came down a scientific route, from Lavater to such varied practitioners as the chief of the identification service of the Paris police during the Commune, Alphonse Bertillon, or the English polymath (inventor of the weather map) Sir Francis Galton. Other elements of physiognomic thinking were less empirical than these, and stemmed ultimately from Swedenborgian mysticism.

Physiognomy (and phrenology as an aspect of it) became associated with a (very Victorian desire) for social control. Certainly, Bertillon was convinced as late as the 1870s that if you could only amass detailed physiognomic information about enough specific criminals, you could begin to draw conclusions that would be valid for genera or types. He believed that you could measure a person’s vital statistics and be able to predict criminal tendencies in advance. In other words, Bertillon argued that the shape of a man’s head could reveal infallibly a tendency towards murder or other crimes against the person or crimes against property. From that, it was only a matter of amending legislation before preventative arrest and incarceration might put the (bourgeois, moneyed) citizens at ease. This is uncomfortably close to nasty ideas along the lines of eugenics (and survived notably as a set of anthropological ideas underpinning a certain facet of European colonialism). By the 1840s the specific vogue for phrenology was beginning to diminish. But thinking along these lines didn’t disappear. It became subcutaneous, a set of prejudices. And it did so at precisely the moment when photography was getting into its unstoppable stride.

My sense is that photography simply absorbed a chunk of phrenology. We to this day still think we can read in faces sure evidence of character. There is a certain code: thick, fleshy lips signify coarse appetites; eyes ‘too close’ together suggest untrustworthiness and so on. Highbrow has even become quite openly a word of character not of anatomy. It suggests intellectual rigour, even a touch of condescension for the ordinary run of life. None of these make any sense: you actually don’t know a person until you know him, whatever your prejudice may suggest. And you don’t ever really know a person simply from a photograph.

The person with the highest brow I’ve ever seen is Gervinho, the (potentially marvellous) Ivoirien forward recently hired by the Arsenal football club. I have never met Gervinho, and I certainly don’t want to fall into precisely that automated thinking that I am referring to here, but I doubt that he spends much of his time reading the Arcades Project in German.

This is what Marcus Coates’ shaving cream points us towards. By softening and changing the factual map of his face, it not only makes it impossible for us to read his character; it makes us acutely aware of how hard we look for precisely the kind of legible hints I have been describing. Part of my fascination with British Moths, 2011, is that I found myself looking much harder at it than I might have done sans foam, in some kind of attempt to see if I could beat the foam at its own game and read character in spite of it and through it. It helps in this context that it’s a self-portrait, too. I don’t think there would have been much interest in photographing a model in shaving foam. It would have been just a temporary costume, a mask. Whereas on the features of the person who is both model and artist, it takes a real place in that complicated dance between the model trying to project one view of himself and the artist trying to reveal perhaps another.

Lots of photographers have used masks, of course. Sometimes they use physical masks of the balaclava helmet variety, and sometimes they mask by photographing with clarity obscured one way or another.

Erwin Blumenfeld, a photographer of much greater psychological shrewdness than most, used both strategies frequently and with mastery. Not at all above putting a paper bag over his own head, he was also fascinated by the whole range of screening effects that could be achieved: he loved photographing through bobbly glass and semi opaque materials, and was a genius at double and triple printing to accentuate and conceal as he required.

Coates has done his masking with shaving foam. It should be ridiculous, childish. But the material itself has marvellously evocative fluidity, such that it becomes a strong element of the success of the piece as a whole. The reshaping of these heads has the perfect immediacy of terracotta, particularly those terracotta studies made (often pending the client’s approval, or just as maquettes to help get the masses right) before a final version in much chillier, more forbidding marble.

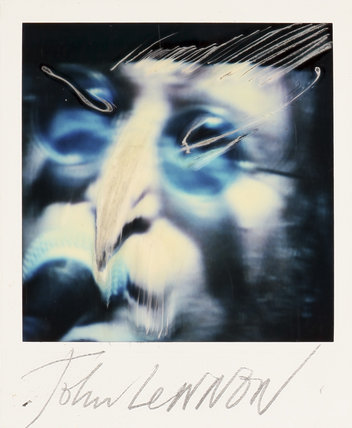

Coates’ shaving foam is lively, seductive. Some years ago the great illustrator Ralph Steadman made a series of portraits on Polaroid SX-70, manipulated in the few moments before it set. They had a kind of energetic line which many mistook merely for violence, but which was really much more to do with how much or how little character could be grasped in a glance. Steadman called these things Paranoids, and they are something of a precursor of Coates’ shaving foam.

Coates has done a wonderful thing. By daring the slightly silly feat of smearing himself in squirty gloop, and by having the very considerable artistic judgment to control and make sense of what happened when he did, he has made a really big artwork. His foam flings us right back in the history of portraiture. The foam offers hints of a person inhabiting it, and then contradicts itself. It invites us to stare hard at it, and then laughs at us doing so.

When I brought up the fact that there were pobmlers for Coates on B&B, I got a lot of static because of the scent of the cream. Tea tree and rosemary is not a combination that tends to jump out and please everybody.Unfortunately.

LikeLike